By T.S. Akers

An English Masonic historian recently referred to Albert Pike as a “peddler of Masonic degrees.” Though the remark was made in jest, Freemasonry in the 19th century certainly had its host of men “peddling” higher degrees to any Mason willing to pay for them. And to some extent, this still occurs today. Albert Pike, however, took the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry and transformed it into a real powerhouse in the realm of Masonic Rites beyond the Craft degrees. With his knowledge of numerous languages, including Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, Pike rewrote the rituals of the Scottish Rite, thus transforming the Order. The details of Pike’s life are related in Walter L. Brown’s volume A Life of Albert Pike and need not be recounted here. But Pike’s relationship with the Indian Territory is worth exploring further.

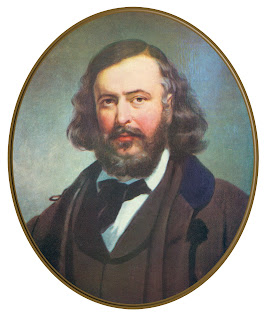

Albert Pike was born in Massachusetts on the 29th of December, 1809.[1] An intelligent young man, he mastered the pass examination for Harvard University in 1825 but was ultimately unable to pay the tuition. Pike then engaged in a program of self-study whilst teaching school, completing the coursework for Harvard independently. Securing enough subscribers, he opened a private school in 1829. With dreams of amassing a fortune, Pike left Massachusetts for the West with several friends on the 10th of March, 1831. The group met Charles Bent of Bent, St. Vrain and Co. in St. Louis that August and joined his latest fur trading expedition to Santa Fe. After much difficulty, having departed far too late in the season, the expedition arrived in Santa Fe late that November, where Pike remained for nine months clerking for Bent, St. Vrain and Co.[2]

As if one bad expedition was not enough, Albert Pike embarked on a far more doomed beaver trapping expedition in August of 1832. The group was to go beyond Taos, into the Llano Estacado region. Unfortunately, this flat tableland was nearly waterless and devoid of game. Pike encountered Comanches along the way before quitting his companions. On the 12th of October, he and four others decided to head east for Fort Towson. By November they arrived at the confluence of the Wichita and Red Rivers, where they encountered an Osage encampment.[3] After crossing the Clear and Muddy Boggy Rivers on the 30th, the party encountered a group of Choctaws chopping down a tree filled with a beehive. Pike attempted to barter for some honey, but the Choctaws refused. This caused Pike to remark that “A Choctaw is without exception the meanest Indian on earth.”[4] Through a navigational error, Pike and his comrades ended up on the road to Fort Smith and arrived at the Choctaw Agency on the 9th of December. Pike estimated that at least 650 miles of the 1400-mile journey from Taos had been completed on foot.[5]

In Fort Smith, Albert Pike returned to what he knew and that was teaching. Hearing of an open position at Fort Gibson, he set out on foot to apply for the job but upon arrival learned that the vacancy had been filled. Pike then established a private school at Van Buren, Arkansas, in March of 1833. He left the field of education that October and set out for Little Rock where he was to join the staff of The Arkansas Advocate, ultimately becoming the paper’s editor. Pike’s tenure in this role was brief as he decided in early 1834 to become a lawyer, like many of his acquaintances. He pursued this change of course by reading the law, consuming in their entirety Kent’s and Blackstone’s Commentaries, and applying to a judge for a law license. Pike was admitted to the bar in August of 1834.[6]

When the United States went to war with Mexico in April of 1846, Albert Pike was serving as captain of the Little Rock Guards. Reluctantly, he stepped away from his law practice to lead his company to Mexico. Whilst many troops headed south passed through Fort Towson, the Arkansas Mounted Rifles did not, instead marching to Shreveport and then on to San Antonio.[7] The regiment was commanded by Colonel Archibald Yell, the second governor of Arkansas and the eleventh Grand Master of Masons for Arkansas.[8] It was noted that Yell’s “Mounted Devils” lacked discipline and that Pike was one of two officers that regularly drilled their companies enroute to Mexico. With Pike and John Preston’s companies being the best drilled, they were formed into a special squadron under Pike’s command. This squadron was permanently detached from the Arkansas regiment in January of 1847 and placed under the command of Brigadier General John E. Wool at Saltillo.[9] Col. Yell would fall at the Battle of Buena Vista on the 23rd of February, 1847.[10] When the regiment returned to Arkansas that summer, there was much animosity between Pike and Lieutenant Colonel John S. Roane, who succeeded Yell as commander of the Arkansas Mounted Rifles. Pike was vocal about the discipline issues within the Arkansas regiment, whilst Roane claimed Pike’s squadron was not present at the Battle of Buena Vista, though General Wool and his staff very much were. The feud led to a duel between the two on the 29th of July, conducted on a sandbar in the Arkansas River, opposite Fort Smith, in the Cherokee Nation. After two rounds of shooting, neither party had been struck. The duel was stopped at the urging of each party’s surgeon and the matter was never discussed again.[11]

The course of Albert Pike’s life was forever changed when he took the degrees of Freemasonry in Western Star Lodge No. 2 at Little Rock in 1850. Having a background in education, he was part of the committee which obtained a charter to form St. John’s College at Little Rock that year.[12] The school was the first institution of high learning in Arkansas and was operated by the Freemasons until 1878.[13] Pike, having taken the Capitular degrees, was a member of the convention which formed the Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons of Arkansas in 1851. He took the degrees of Royal and Select Master in 1852 and the Templar orders in 1853. It was also in 1853 that Pike took the degrees of the Scottish Rite at Charleston, South Carolina, and was coroneted a 33rd Degree in that rite in 1857.[14] In August of the following year, a Scottish Rite Consistory was established at Little Rock.[15] Pike assumed the office of Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite’s Southern Jurisdiction in early 1859, a role he would remain in for the duration of his life.[16]

Throughout the 1850s, Albert Pike embarked on a journey as a lobbyist for the Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Muscogee (Creek) Nations. Pike was visited by Creek Agent Philip H. Raiford in 1852 who asked Pike to pursue a claim against the federal government for lands confiscated under the Treaty of Fort Jackson in 1814. Pike thoroughly reviewed the details of the treaty and had Arkansas Congressmen Robert W. Johnson present the findings to the House of Representatives, who referred the matter to committee. Indian Commissioner Luke Lea confirmed to the Committee on Indian Affairs that the Muscogees were in fact due compensation for over eight million acres that was confiscated. An amendment was drawn up for the general appropriation bill for Indian Affairs to provide for the $1,769,880 due the Muscogee Nation, but it was defeated in February of 1853. Pike returned to Congress in December of that year, to present the Creek claim again, this time in the Senate. Robert W. Johnson had been appointed to the Senate that summer and his counterpart from Arkansas was Pike’s friend William K. Sebastion. In considering the claim, the Senate sought to arbitrarily reduce the compensation to $500,000 and ultimately failed to act on the matter.[17]

During this period, Albert Pike became aware that the Choctaws and Chickasaws had a claim to recuperate individual expenses arising from removal after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830. That claim was being handled in late 1853 by the then former Indian Commissioner Luke Lea. Meeting with Choctaw headman Peter P. Pitchlynn, Pike secured a contract to represent the Choctaws and Chickasaws under the same terms as the Muscogees, with a twenty-five percent fee. In his research, Pike determined that the best solution for the Choctaws and Chickasaws was a new treaty, as proving the individual claims was nearly impossible. With a desire to settle a political quarrel between the Choctaws and Chickasaws, separating them into two independent governments, the United States signed the new treaty in 1855. This treaty required a payment of $800,000 to the Choctaws and Chickasaws for land cessions and Pike personally saw that it was ratified by the Senate in February of 1856.[18]

When it was deemed prudent to politically separate the Seminoles from the Muscogees in the summer of 1856, Albert Pike urged the Muscogees to require the claim from the 1814 treaty be addressed. Pike’s insistence prevailed and the treaty ratified that August in 1856 called for the Muscogee Nation to receive $1,000,000 for its land claim. To receive the payment for his fee after the initial appropriation of $800,000, Pike spent three months in the Muscogee Nation beginning in June of 1857 as a guest of Muscogee headman George W. Stidham.[19] It was during this visit that Pike attended the St. John’s Day observance at Muscogee Lodge No. 93, located at the Creek Agency, the lodge where Stidham held membership.[20] When Congress appropriated the remaining $200,000 due the Muscogees, Pike returned for subsequent payment in September of 1858, again staying for several months.[21]

A recent discovery by Bro. Kenneth Sivard, a former Grand Historian for Oklahoma, is a curious letter from Albert Pike to Peter P. Pitchlynn dated the 30th of August, 1859. The letter is addressed to “My Dear Sir Knight and Brother,” referring to Pike’s Masonic connections to Pitchlynn and indicates Pike is preparing to depart for Chicago for the triennial sessions of the General Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons and the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar that September.[22] Pike was Grand High Priest of Royal Arch Masons for Arkansas in 1853.[23] In the letter, Pike remarks upon how he has worked to serve and defend the Choctaw people. Having been written upon the eve of the American Civil War, the letter takes an interesting tone, with Pike adding, “I am weary of life in this state - weary of the ignoble controversies that here make up men's lives.” Pike goes on to ask that the Choctaws adopt him and his family as citizens, even including legislative text for Pitchlynn to introduce to the Choctaw General Council.[24] A review of the transactions of the Choctaw Senate from October of 1859 reveals that Pitchlynn never introduced Pike’s proposed resolution for citizenship. The two men became lifelong friends and Pike personally made Pitchlynn a 32nd Degree Mason in 1860. Pitchlynn was in Washington, D.C., when he passed away in 1881 and was laid to rest in Congressional Cemetery, with Pike delivering the eulogy at his service.[25]

After the secession of Arkansas from the Union in May of 1861, Albert Pike immediately looked to the Indian Territory for the defense of the state’s western frontier. Aware of Pike’s status with the Muscogees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs promptly forwarded Pike a commission granting him the authority to establish treaties of alliance with the Indian Nations. In his official capacity, Pike entered the Indian Territory in early June, to first court Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross. The Cherokees being not easily persuaded, Pike went on to North Fork Town to negotiate with the Muscogees.[26] It was then that the pieces began to fall into place as treaty negotiations proved fruitful. By August of 1861, treaties had been signed with the Muscogees, Choctaws and Chickasaws, and Seminoles. The Cherokees, along with several other tribes, agreed to treaties by that October. The key takeaways from the treaties where the continuation of annuity payments the federal government had stopped making, representation in the Confederate Congress, the continuation of slavery, and the raising of Indian regiments for Confederate service.[27]

In November of 1861, Albert Pike was granted the position he originally hoped to receive, which was commander of the Department of the Indian Territory as a brigadier general.[28] In this capacity, Pike erected Fort Davis on the southern banks of the Arkansas River, establishing his headquarters there.[29] Whilst Pike had hopes that his command would be independent, he soon found himself under the purview of Major General Earl Van Dorn. When Confederate troops were pushed from southwestern Missouri, Van Dorn began work on a counteroffensive to prevent northern Arkansas from falling into federal hands.[30] In preparation for a battle near Fayetteville Van Dorn ordered Pike to move his command to near Elm Springs, placing them in the rear of Van Dorn’s army.[31] Pike’s Indian troops initially refused to begin the march to support Van Dorn, but were induced to do so after receiving back-pay they were due, an indication of things to come.[32] The ensuing engagement which occurred on the 7th and 8th of March in 1862 would become known as the Battle of Pea Ridge. After the delays concerning pay, Pike arrived in the field and went into battle with only Stand Watie’s and John Drew’s Cherokees, as well as Otis Welch’s squadron of Texas cavalry.[33]

The Battle of Pea Ridge resulted in a Confederate defeat and Albert Pike’s ability to command was called into question. On the 7th of March, Pike’s troops captured a federal battery near Leetown, became disorganized, and were then pinned down for the duration of the day by another federal battery. In the resulting chaos, one Indian trooper killed a wounded federal soldier. After the engagement, it was reported that some federal soldiers had been scalped, with the northern press claiming at least eighteen had been found in such a condition. Officers from the 3rd Iowa Cavalry reported the number scalped to have been eight. To ascertain the truth, Pike consulted with surgeon Edward L. Massie, who had attended both federal and Confederate wounded on the field near Leetown. Massie confirmed that he found "one body which had been scalped; evidently after life was extinct." Pike immediately issued an order to his command rebuking them for the “barbarous and wanton killing” of the wounded and the practice of scalping.[34] Unfortunately, the scalping incident cast a shadow over Pike and the discipline of his troops.

Returning to the Indian Territory, Albert Pike moved his command south, where his next challenge would arise. Pike had been advised by Earl Van Dorn to maintain a presence in the northern portion of the Indian Territory but not to expect any support from Arkansas. Pike’s move south was prompted by this lack of support, which led him to believe the Arkansas River was no longer defensible. Leaving Colonel Douglas H. Cooper in command at Fort Davis, Pike withdrew to the Blue River where he erected Fort McCulloch, named for the late General Benjamin McCulloch, not far from Fort Washita. This new post had no real strategic value and it was said that Pike had, “…constructed fortifications in the open prairie, erected a sawmill remote from any timber, and devoted himself to gastronomy and poetic meditation...”[35] In May of 1862, Pike found himself reporting to Major General Thomas C. Hindman, who had assumed command of the newly re-organized Trans-Mississippi Department. Pike believed his command should have been independent and receiving no aid from Arkansas certainly heightened this feeling. With federal troops pouring into Arkansas, Hindman ordered Pike to send his white infantry and one six-gun battery to support Little Rock. Pike, contending that Hindman’s area of command was too broad and “giving orders at a distance,” begrudgingly dispatched the requested troops in early June.[36]

With nearly all the Confederate forces in the Indian Territory positioned south of the Arkansas River, the Cherokee Nation felt as if they had been abandoned and by the end of 1862 would negate their treaty with the Confederacy. To remedy the situation north of the Arkansas River, Thomas C. Hindman ordered Albert Pike to move his remaining white troops to Fort Gibson in mid-June. It was at this time that Pike ratcheted up his feud with Hindman, which originated with pre-war politics. In a series of dispatches, Pike claimed that Hindman was crippling his command and that rifles bound for the Indian Territory had been diverted to Little Rock.[37] Pike’s command was indeed poorly supplied, with one of his regimental commanders noting that powder rations were miniscule and that the men lacked proper shoes and clothes.[38] That July, Hindman expanded Pike’s command to include northwest Arkansas, ordering Pike to Fort Smith. Pike refused this order, stating the best he could do is “hold the Choctaw and Chickasaw country” if the federals invaded the Indian Territory. Pike then resigned and Hindman gladly forwarded the resignation to Richmond. Before the resignation could be accepted though, Pike issued a circular across the Indian Territory alleging that Hindman was subordinating the defense of the Territory to “the interests and safety of Arkansas.” Viewing the circular as an act of treason, Douglas H. Cooper ordered Pike arrested, but he slipped away into Texas.[39]

Albert Pike’s resignation that July of 1862 did not actually conclude his service with the Confederacy. Having evaded arrest, he intended to go to Richmond to bring charges against Thomas C. Hindman. On the 16th of July, Hindman was replaced as departmental commander by Major General Theophilus Holmes. Learning of this, Pike hurried to Little Rock to make his complaint against Hindman for interfering with his command in the Indian Territory. Pike found no sympathy with Holmes but did learn that his resignation never arrived in Richmond as the courier carrying it had been captured. Pike resubmitted his resignation and requested leave. Believing his resignation had been rejected, Pike proceeded to Fort Washita from Texas in early October to resume his command. Unfortunately for Pike, his resignation had been accepted, and it was alleged that he had interfered with troop movements in the Territory and detained ammunition in Texas. Pike was once again ordered to be arrested and was taken into custody near Tishomingo for transport to Warren, Texas. Lacking evidence of wrongdoing, Pike was ultimately released and returned to Little Rock.[40]

Leaving Little Rock, Albert Pike spent the duration of the War quietly residing in a cabin on the Little Missouri River. He briefly served as an associate judge for the Arkansas Supreme Court, beginning in the spring of 1864. After the Trans-Mississippi Department surrendered in late May of 1865, Pike started for Mexico with his family. Separating himself from the United States, as he had considered when pursuing Choctaw citizenship in 1859, clearly remained a thought Pike was willing to entertain. Instead of a life in Mexico, Pike chose to go north to Washington, D.C., after confirming federal officials would not molest him.[41] In the federal capital, Pike was granted a presidential pardon, that was largely obtained through the efforts of Benjamin B. French; the Commissioner of Public Buildings and Sovereign Grand Inspector General for the Scottish Rite in the District of Columbia. Pike refused to accept the pardon owing to stipulations attached to it.[42] During a visit to the White House by Scottish Rite dignitaries on the 23rd of April, 1866, President Andrew Johnson quietly handed Pike a sealed envelope, containing a more complete pardon than the original.[43]

It does not appear that Pike ever gave another thought to becoming a Choctaw citizen. Outside of an over twenty-page open letter “To the People of the Choctaw Nation” penned in 1872, concerning the treaty negotiations Pike handled for them, he likely never considered the Indian Territory at length again. After the moving of the Scottish Rite’s Supreme Council headquarters to Washington, D.C., in 1870, where Pike took up residence until his death, the distance between him and the Indian Territory certainly grew. Pike addressed the Indian Territory one last time in 1889, that being when he appointed Robert W. Hill of Muskogee as Deputy for the Supreme Council.[44]

No comments:

Post a Comment